A R T

2 0 1 8 T U S C A R O R A R E V I E W

1 7

1 6

T U S C A R O R A R E V I E W 2 0 1 8

S T O R Y

A GRAVEYARD ON THE HILL

Christopher Rahman

F

our new graves needed to be dug. An arduous task for the gravedigger, even

without frozen ground that could dull any shovel. But the weather had

turned, as there was no longer a chill in the air. There was a bite. Still, the

gravedigger set about his task as usual though his grip was tighter, and he dug

with an unsuspected vigor. Death may not wait, striking a person whenever

she pleases, but these four would have to. The priest had brought them to the

hilltop church for the service and the burial. There were two adults and two

children. The priest had left as they had arrived. With the entire family gone,

there was no one left to mourn. But more importantly for the church and the

priest, there was no one left to pay.

The priest walked away from the comfort of his church after a brief time. He

wore a thick, wool coat and prayed it was enough to hold back the cold. His coal

black hair, slicked back, was hidden beneath a wool cap, and his usually pale

skin was flushed red in the wind. The cold of winter’s breath had no mercy. He

scanned the church’s substantial graveyard. The gravedigger was there most

days, even when no graves needed to be dug, tending to all those long forgotten

by the world above. The priest found him, eventually. Even amongst the dead,

the man did not stand out. He was dressed to fight the winter air, his large

coat disguising his slight frame. He looked to be middle-aged, his brown hair

streaked with grey. The rough leather of his skin revealed a man who spent too

much time in the sun. His eyes betrayed his youth. They were a piercing blue,

bright. The priest’s eyes, which were coloured the dark grey of storm clouds,

were dull in comparison.

“Good morning,” the priest said, no conviction in his words. The gravedigger

had stopped his work. The priest looked at the four coffins, two were adult-

sized and the others were much smaller. “They were found by the roadside,

their wagon ransacked. A family traveling somewhere from some place.” The

gravedigger nodded.

“There wasn’t any sort of identification on the bodies, so we couldn’t contact

any family. No one’s going to visit them,” the priest continued looking around,

as if searching for someone, then looked back at the gravedigger. “It’s rough out

here. You can just throw them all into one grave if you need to. No one would

care.”

“I would.” The gravedigger went back to his grim task.

The priest let out a breath. “God can be cruel.” He turned and walked away.

The gravedigger said nothing. His hands gripped the shovel tighter. His jaws

clenched. He should be unaffected by the priest’s callous attitude, had faced

it almost every day and even understood it. The priest had to take care of his

congregation. He could still alter their lives. The dead were dead and would

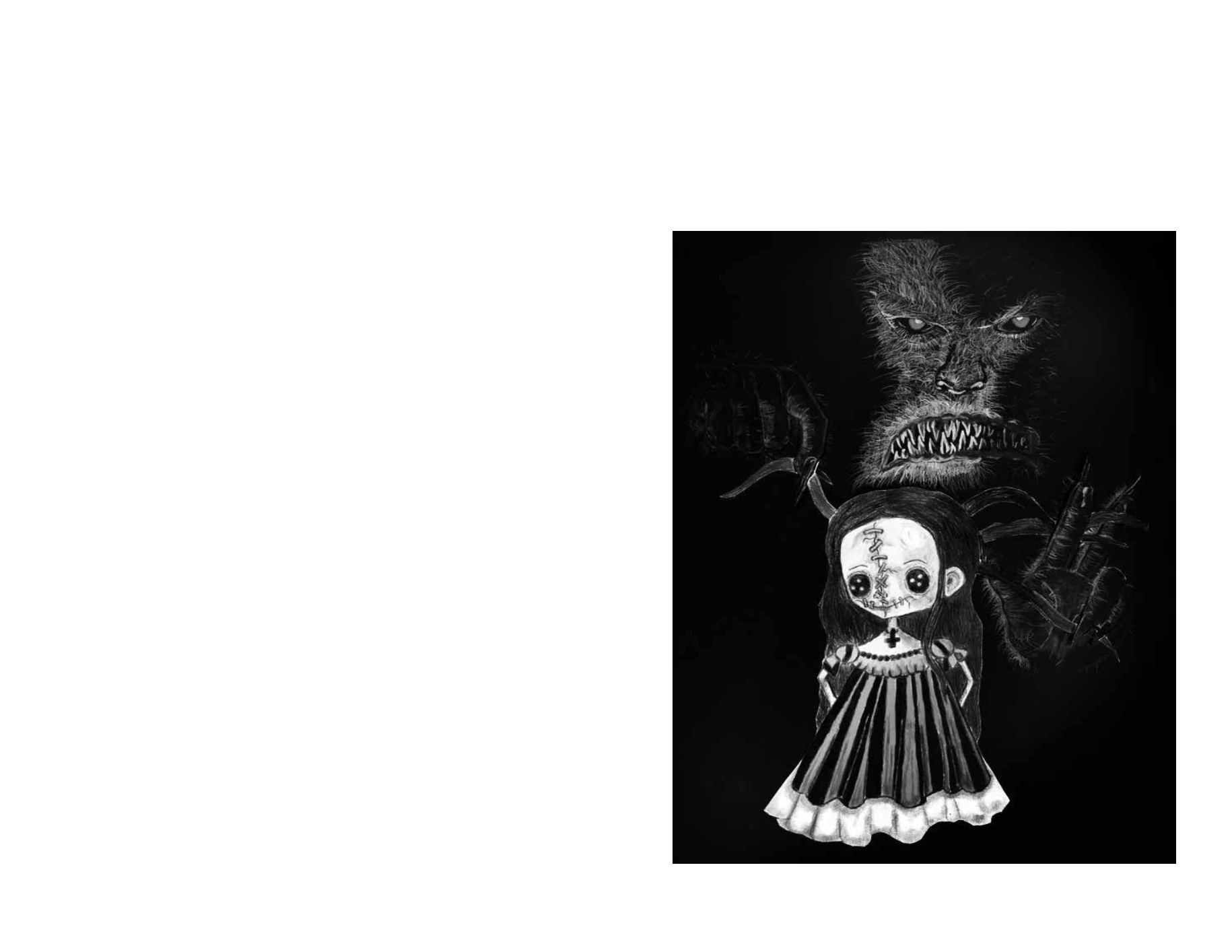

Marco DeLauri, Possessed Things – Illustration

always be. It made sense. At least it should, but the gravedigger had dealt with

the dead most of his life and he knew all those gone had been a person, alive

in memory or not. So even in the bitter cold, four graves would be dug. The

gravedigger’s shovel barely broke through the frozen ground. The graves would

take time, so the gravedigger prepared for a long day. It was easy, with only the

dead for company, to get lost within oneself.

The gravedigger had been a farmer’s son, in a farmer’s family. He had two

older brothers, and they all ran the farm together with their father. Too young